Why you should think of your adviser as your personal financial trainer

Growing up we had one of those indoor exercise bikes. You know the type, the ones you purchase with dreams of sweating off the pounds and getting into top shape. It came one day in a big cardboard box. We unwrapped it, marveled at it, sat on it and spun the wheels… and then mostly treated it like a piece of artwork. It was there to be admired but not touched.

I don’t know if anyone else has had a similar experience, but my fitness regime using the exercise bike (artwork/clothes hanger) was in stark contrast to a former colleague who worked with a personal trainer. Month by month, spin class by spin class, I could see him getting fitter and fitter.

Of course, a personal trainer should know a tremendous amount regarding the human muscular skeletal system and exercise techniques. But I don’t think the trainer’s technical acumen was the reason they worked together. I mean, I’m sure the technical skill was valuable, but, honestly, if we want to get into shape, we all know how to ride an exercise bike, right?

The problem most of us have isn’t that exercise is too complicated or the human body too difficult to understand. For most of us the issue is the motivation to exercise consistently in order to achieve the desired results.

In other words, the value of the personal trainer probably has more to do with the discipline of consistent exercise, than with the technical nature of how to correctly perform the exercise. And, for my former colleague, this discipline outweighed any other benefit, especially when compared to the stopping, starting, chopping and changing most of us go through when left to our own devices.

There is evidence of this value. In an academic article in the Journal of Sports Science & Medicine titled “The Effectiveness of Personal Training on Changing Attitudes Towards Physical Activity”, the author claims that “one-on-one personal training is an effective method for changing attitudes and thereby increasing the amount of physical activity. Secondly, it seems that using problem-solving techniques is of value for successful behavior change.” (1)

As with a personal trainer, it’s a financial adviser’s job to change their client’s “attitudes” and provide key “problem solving” techniques that improve their client’s financial health.

Ben Graham, who wrote one of the most referenced books on investments titled The Intelligent Investor, once quipped, “An investor’s chief problem – and even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself”.

Graham, who died in the 1970’s, would not have heard of behavioural finance. But he knew by experience what hundreds of academic articles have subsequently proven regarding poor investor behaviour.

In a 2011 paper titled “The Behaviour of Individual Investors” (2), Professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean summarise two decades of work into the poor performance of individual investors.

Their five conclusions were that, in general, individual investors:

- Underperform standard benchmarks (e.g. a low cost index fund)

- Sell winning investments while holding losing investments (the ‘disposition effect’)

- Are heavily influenced by limited attention and past return performance in their purchase decisions

- Engage in naïve reinforcement learning by repeating past behaviours that coincided with pleasure, while avoiding past behaviours that generated pain

- Tend to hold undiversified share portfolios

They state, “these behaviours deleteriously affect the financial well-being of individual investors”.

In fact, there have been significant efforts made to quantify the impact on investors who reject a buy and hold market portfolio and instead allow their decisions to be influenced by fear, hunches, intuition, hope or even greed.

Professor Barber himself wrote a study which showed that individuals trading portfolios underperformed the broad market by 3.8% a year (3).

Financial research company DALBAR, has also attempted to quantify the effects of poor behavior on investors’ long term returns. According to their 2016 study (4), the average individual investor underperformed the broad sharemarket by 2.89% over the past 20 years.

DALBAR made the following observation:

"Investors lack the patience and long-term vision to stay invested in any one fund for much more than four years. Jumping into and out of investments every few years is not a prudent strategy because investors are simply unable to correctly time when to make such moves."

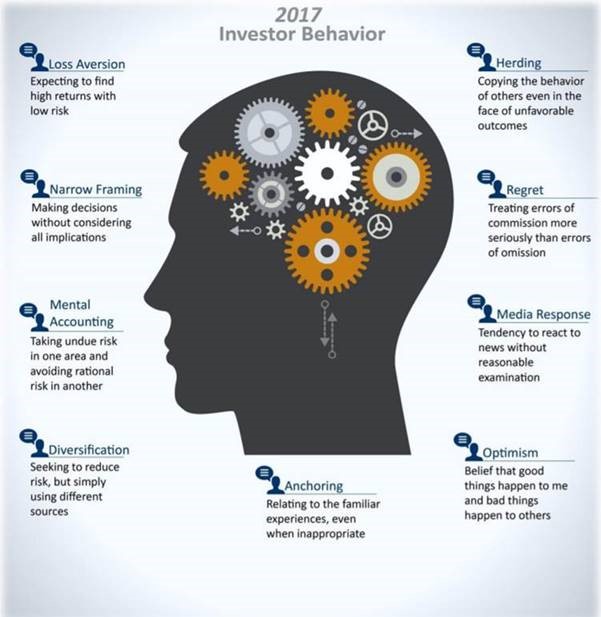

In the image below, DALBAR noted nine behavioral reasons why investors have done so poorly, which an adviser must systematically try to correct.

The job of an adviser is to counteract each of these common biases which will otherwise undermine good, sound, long term investment decision making. And, as supported by the DALBAR (and other) research, this is often the greatest value an adviser can deliver.

As the saying goes, “We don’t have people with investment problems; we have investments with people problems”.

To change behaviour, an adviser must help each client define what they really want their money to achieve for them in life. The adviser must then substantially increase the probability that their client is able to achieve those outcomes. The key is to help clients make smarter investment decisions and prioritise what matters to them the most. The best advice is honest and sometimes confronting, but it is decisive and adaptable to changes in markets and lifestyle.

It's not that investing is difficult, it’s just difficult for most individuals to do it consistently well. Like exercise, it’s not about making a big effort every once in a while. Great advice is best to be implemented consistently and carefully over a long period of time.

Investors would do well to think of their financial adviser as their personal (financial) trainer. Not just because an adviser is more likely to help us make better long term investment decisions, but because he or she will keep us motivated and on track when we might otherwise succumb to poor behaviour.

After all, it’s a bit harder to say, “Exercise? I thought you said extra fries” when your personal trainer is on your team.

Ben Brinkerhoff

Head of Adviser Services

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3937569/

- Barber, Brad M and Odean, Terrance, The Behavior of Individual Investors (September 7, 2011).

- https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article-abstract/22/2/609/1595677

- https://svwealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/dalbar_study.pdf