What REALLY adds value when you choose a KiwiSaver scheme?

We’ve all seen it, the advertisements that go something along the lines of,

“XYZ Scheme is the highest performing KiwiSaver fund for the last 5 years”.

The implication of the advertisement is simple, recent performance is the singular piece of information most important in selecting your KiwiSaver fund.

But is it? With 15 years of KiwiSaver returns data now, we can really start to zero in on what really adds value when you choose a KiwiSaver scheme. Hint, it’s not recent returns.

Looking at the last 15 years of returns data for KiwiSaver this article will ask three questions:

- Does switching KiwiSaver managers based on performance help or hurt subsequent performance

- Does switching KiwiSaver managers based on fees help or hurt subsequent performance

- What’s the impact of allocation to shares, bonds and cash on overall KiwiSaver performance

When asking these questions, I’m going to be ambivalent about the myriad other issues you might consider before changing providers such as convenience, service, quality, and readability of information, etc. These things matter, but the data doesn’t inform me on those topics, and I want to focus in on the questions posed above.

So firstly, does changing KiwiSaver based on performance really give you better outcomes?

To assess this question, we’ll look exclusively at the Morningstar category “Aggressive Allocation” which includes funds that have a much higher proportion in shares than bonds and cash. It’s the natural category to use when overall performance is the key metric.

Within this category, I’ll define four behaviours an investor may have about returns which I’ll call Holding, Chasing, Avoiding, and Random.

- Holding: This investor choses a random fund at the start and never changes.

- Chasing: This investor looks at the last 12 months of cumulative returns and selects one of the 10 best performing funds every 12 months as if trying to chase good returns.

- Avoiding: This investor looks at the last 12 months of cumulative returns and selects one of the 10 the WORST performing funds every 12 months as if trying to avoid good returns.

- Random: This investor randomly selects a new fund every 12 months.

If I run this test 100 times, which of the four behaviours listed above will on average end up with the highest balance? You’d probably believe “Avoiding” would lead to the highest balance, wouldn’t you? How could choosing a fund based on which ones performed badly be a good approach? Intuitively the “Chasing” category seems most appealing. At least you’re not selecting at random. Having some info is better than sticking you’re finger in the air, isn’t it?

We’ll here’s the result.

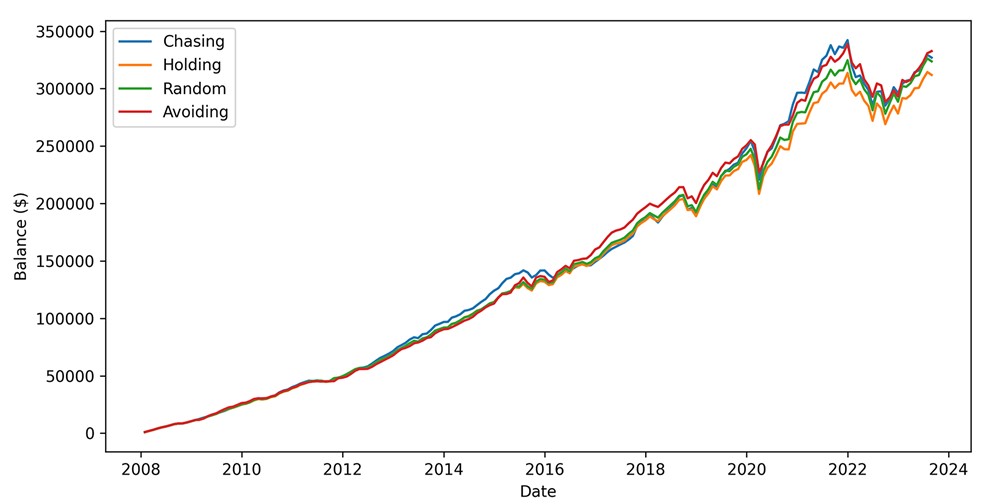

This chart, as the others in the article assume that at the start of each month, investors add a constant amount of money (in this case $100) into their portfolios.

So, what are we looking at? Each line of the chart represents the average return from our four behaviours, ‘holding’, ‘chasing’, ‘avoiding’ and ‘random’. The chart also shows in blue the range of outcomes for the 100 trials of ‘chasing’. In some trials ‘chasing’ did well in others it did poorly. The bold ‘chasing’ line in dark blue is the average of all the trials.

So, what inferences can you draw from this chart? Well, the lines are all on top of each other. In other words, chasing performance doesn’t really add or detract from value relative to any other behaviour. According to this chart you might expect the same outcome from simply holding your existing scheme or even from selecting a scheme based on recent underperformance. The adage, "Past performance is no guarantee of future results” rings true here. The implication of course is that investors should be sceptical of any advertising encouraging them to switch schemes based on recent performance. Performance chasing does not appear to add value when you choose a KiwiSaver.

That brings us to our second question, does switching managers based on fees help or hurt subsequent performance?

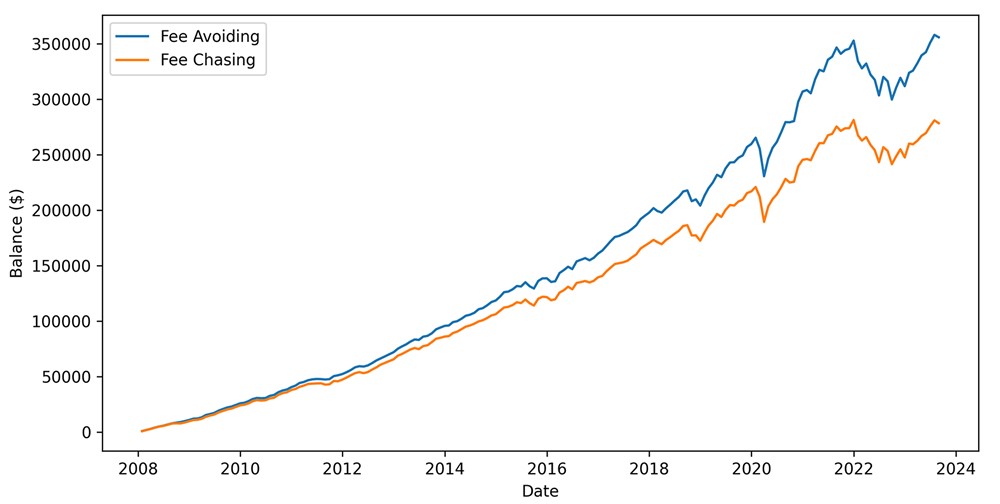

Like the last example, to answer this question I need to create two categories and compare the results.

- Fee Avoider: This investor chooses a new scheme provider every 12 months randomly based on those the lowest cost 10 schemes available. In other words, this investor hates fees.

- Fee Chaser: This investor chooses a new scheme provider every 12 months randomly based on those the highest cost 10 scheme available. By contrast this investor loves fees (why, we’ll never know but it creates a useful contrast to our fee avoider).

Again, we run 100 trials of each strategy and compare the average results. The findings are equally fascinating as those based on performance above. You end up with a meaningfully higher balance if you ‘avoid’ rather than ‘chase’ fees. For most things in life, you get what you pay for. With KiwiSaver, you seem to get what you don’t pay for.

The inference is clear, while recent performance does not add value when choose a KiwiSaver, selecting a scheme with lower overall fees does add value when you chose a KiwiSaver.

But there is an important caveat to the above analysis. In both tests I assume you are in an “Aggressive Allocation” according to Morningstar. Most investors aren’t. According to a recent PWC report on KiwiSaver in Covid, only a very small fraction of Kiwi’s allocates that way. I also assume that you never move to a lower allocation or reduce your contributions due to choppy markets, but some do. I also base “success” here on ending with the highest amount. But that’s not a good definition of success. Success is probably better defined as entering retirement with knowledge that you have all the assets you need both in and out of KiwiSaver, and you are able to have standard of life you are happy with, which gives you a sense of confidence and peace of mind.

To achieve that sort of outcome you should consider getting competent advice. If you get meaningful advice, that’s worth paying for. And good advice might very well suggest lower investment costs and more aggressive allocations. That why recent KiwiSaver entrants like the KiwiWRAP KiwiSaver Scheme are welcome. The KiwiWRAP KiwiSaver scheme encourages true independent advice on your KiwiSaver investment allocations because the adviser is paid by you, and they have freedom to select from over 400 fund and investment options rather than be limited to one fund family. When advisers are paid by you and have more choice, they are more likely to consider your complete objectives and hopes around a secure retirement. In addition, with an engaged adviser, you may be more comfortable taking an allocation with a higher percentage in shares and this can make a big difference in your long-term returns.

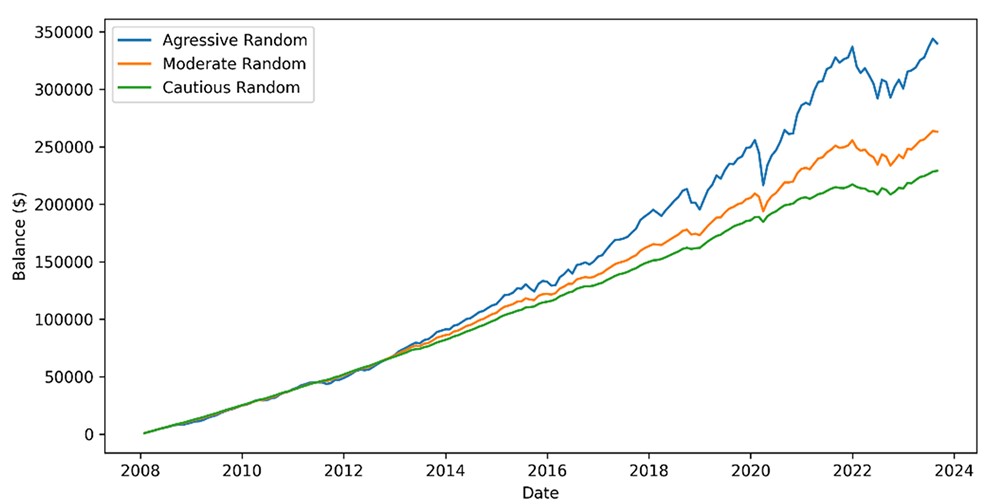

To make this point even clearer, we ran a third test where we selected randomly between schemes Morningstar label as Aggressive, Moderate and Cautious. As a reminder, an Aggressive allocation invests mostly in shares, a Moderate allocation invests about 50% in shares and a Cautious allocation invests mostly in cash and bonds.

So, What’s the impact of allocation to shares, bonds and cash on overall KiwiSaver performance. Results are shown below.

The Aggressive allocation (shown in blue) does much better over time than the Moderate or Cautious fund. You may ask why it takes several years to see a divergence in the performance. This is because early on the regular cash contributions to the scheme have the largest impact on your balance. Over time, as balances grow, your investment performance starts to have a more meaningful impact. This why advice matters more once your balance grows.

But overall, the message here is that asset allocation does REALLY add value when you choose a KiwiSaver. If advice helps you be more comfortable selecting an aggressive allocation appropriate for your age, circumstances and helps you continue to hold the position through choppy markets, it will have done you a lot of good.

I think the implications for this research are clear:

- Choose a fund with the most aggressive allocation appropriate for your circumstance and consider getting advice so your assets are working to achieve your overall objectives for a comfortable and secure retirement.

- Make low fees, rather than recent returns, a more important factor in choosing your KiwiSaver scheme.

- Leave good enough alone! Don’t chase performance or worry if someone else was in the best performing fund over some recent time-period. Chasing probably won’t add value and might give you unrealistic expectations that lead to making worse decisions down the road.